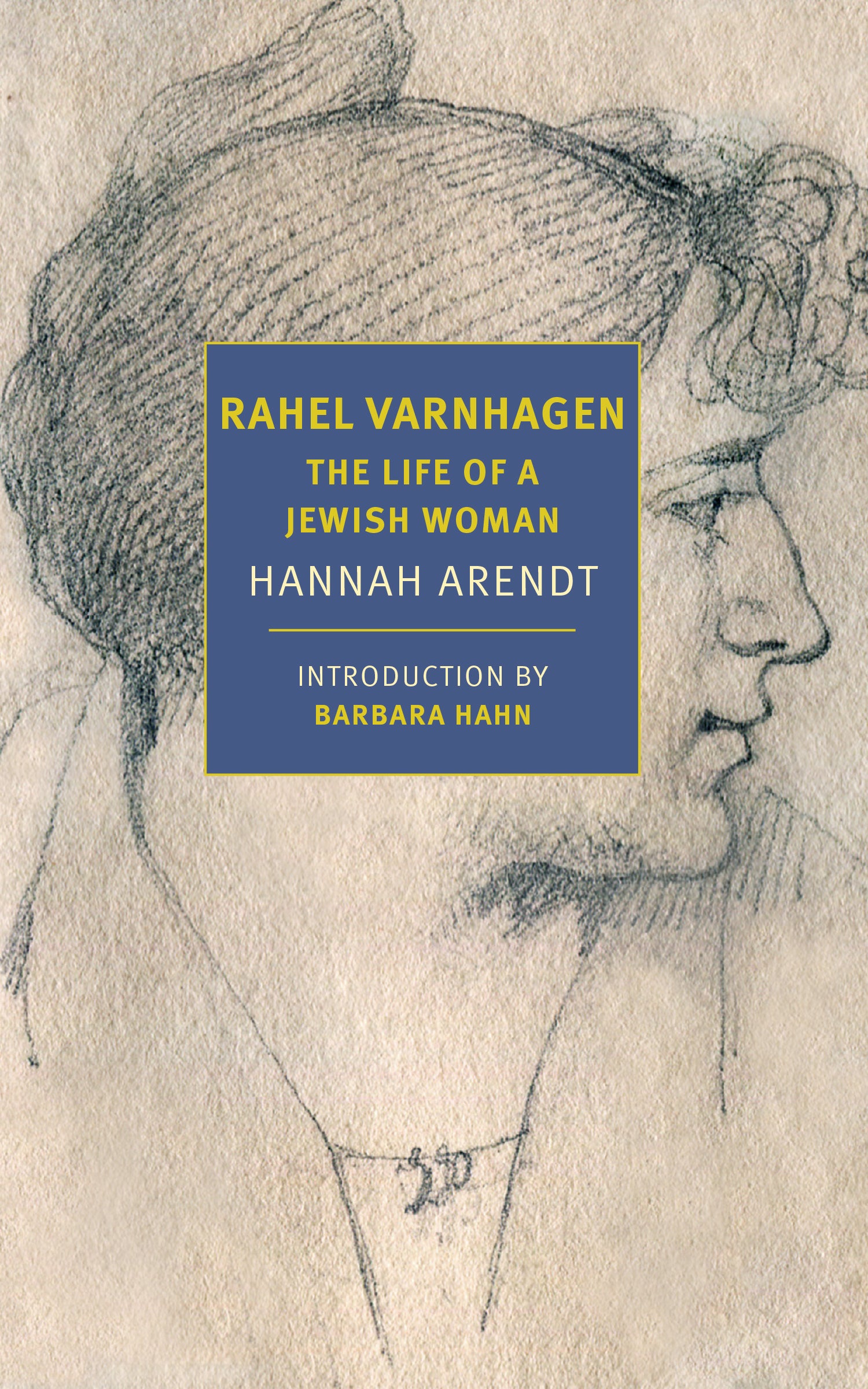

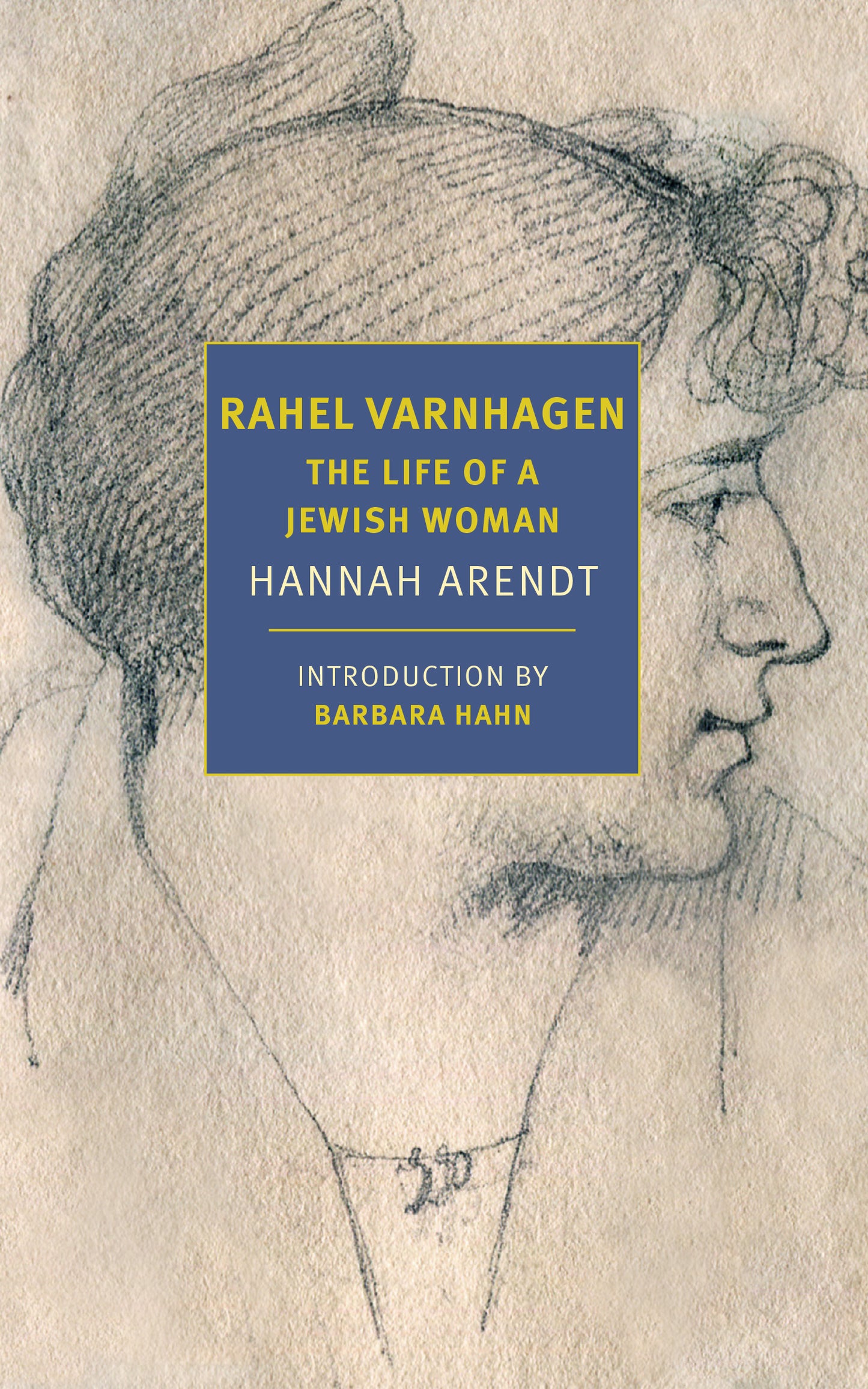

Rahel Varnhagen

Rahel Varnhagen

The Life of a Jewish Woman

by Hannah Arendt, translated from the German by Clara Winston and Richard Winston, introduction by Barbara Hahn

Regular price

$18.95

Regular price

Sale price

$18.95

Unit price

per

Couldn't load pickup availability

Additional Book Information

Additional Book Information

Praise

Praise

-

Shopping for someone else but not sure what to give them? Give them the gift of choice with a New York Review Books Gift Card.

Gift Cards -

A membership for yourself or as a gift for a special reader will promise a year of good reading.

Join NYRB Classics Book Club -

Is there a book that you’d like to see back in print, or that you think we should consider for one of our series? Let us know!

Tell us about it